All images sourced from Wikipedia unless otherwise noted.

What is a workstation? Wikipedia’s definition starts with

A workstation is a special computer designed for technical or scientific applications. Intended primarily to be used by a single user, they are commonly connected to a local area network and run multi-user operating systems.

This definition contains two important demarcations: unlike personal computers (that’s what PC stands for) they are designed for professional applications. But they are not servers or terminals (front-end devices without actual computing power that are used to access a server/mainframe) and put the computing power on or under the user’s desk instead.

The definition elements of being connected to a LAN and running a multi-user operating system are a bit outdated. These were certainly of relevance in the first half of the 1990s, the heyday of the workstation, when PCs used DOS and Windows 3 and lacked both a networking interface and a TCP/IP stack. But thanks to the Internet, all computers are now networked, and even Windows can be considered a multi-user operating system.

So I’d like to propose a slightly different definition:

A workstation is a computer for primarily a single user that is used for professional purposes. It provides more computing resources (CPU and GPU performance, main memory, and possibly storage) than a standard personal computer. Typical applications are scientific and engineering computations, video, and audio processing.

The software categeory for the latter purpose is even known as digital audio workstation (DAW).

Beginnings

Given how expensive early computers were, they were all multi-user – in a sense. With there being one or at most a few computers for an entire company or institution, these were shared among users. Wikipedia lists the IBM 1620 and IBM 1130 as among the first workstations. These were the cheapest IBM offerings in their time and could be controlled by a single user in an interactive manner. A screen (which IBM called Graphics Display Unit) was available for the 1130, but the typical way of using these was by feeding punch cards and printing results. Both supported the Fortran programming language, which in evolved forms is still used today – I programmed in Fortran 90 during my time as PhD student.

During the 1970s, terminals that provided keyboard input and screen output became more common – but these were linked to mainframes running multi-user operating systems that provided the computing power, so these were not workstations. The end of the decade then saw the introduction of the home computer for consumers: the TRS-80, Apple II, and Commodore PET – but these offered neither the performance nor the memory required for professional applications.

Instead, the ancestor of the workstations that arrived in the 1980s can be considered the Xerox Alto. It was technically a minicomputer, not a microcomputer (i.e. considerably large than what would later constitute a desktop computer), but it had features that would later be common: a graphical user interface controlled by a mouse, and ethernet connectivity. In 1979, a certain Steve Jobs of a small computer manufacturer called Apple Computer Inc. visited the Xerox offices. This visit provided much inspiration for the GUI of Apple’s unsuccessful Lisa and the eventually very successful Macintosh.

RISC and UNIX

In 1991, IBM launched the model 5150 Personal Computer (PC), powered by the Intel 8088, a variant of the 8086 processor. Despite the name, it found much more acceptance among business users than home users. Its modest feature set and very basic operating system (DOS, by a small software company called Microsoft) meant that it was more suitable for text processing and spreadsheets rather than the sort of applications that workstations are used for. I still find the 5150 model designation very funny – it’s a Californian code for mental illness and was used by Eddie van Halen as name for a song, an album, his recording studio, and his signature amplifier.

The other common processor family in those days was the Motorola 68000. It is probably known best for powering the more advanced generation of personal/home computers that arrived in the mid-1980s: the Apple Macintosh, Commodore Amiga, and Atari ST. It was also used in professional workstations from makers like Hewlett-Packard (now HP), Sun, SGI – and Apollo.

Apollo was one the biggest name in workstations in the 1980s. Its Aegis operating system was designed for networking from the start. Not offering a true Unix and missing the RISC bandwagon (see below) lead to problems later in the decade, and Hewlett-Packard bought Apollo in 1989.

Another manufacturer worth mentioning who used the Motorola 68000 was NeXT. NeXT was founded by Steve Jobs in 1985 after he had been kicked from Apple. NeXT had its own operation system, NeXTSTEP, which was derived from BSD Unix, had its own graphical user interface, and employed an object-oriented programming language. Sales were limited, but NeXT nevertheless made a lasting impact: Tim Berners-Lee wrote the first web browser on a NeXTcube, and id Software used NeXT machines for Doom and Quake, the games that can be considered the first modern first-person shooter. NeXT was eventually bought by Apple, with NeXTSTEP becoming the basis for Mac OS X, which eventually evolved into both iOS and macOS.

Both the Intel 8086 and the Motorola 68000 processor families are CISC (complex instruction set computer) architectures. This contrasts with RISC (reduced instruction set computer). A RISC system is generally more efficient, but might be slower for certain operations or more difficult to program – but this is a broad generalization, and both architectures are still around.

In the 1980s, RISC was considered to be the way forward my many computer manufacturers. This resulted in a considerable number of new RISC processor architectures arriving on the scene and being used in what now were proper workstations. The most important players were:

- ARM by Acorn, introduced in 1985 but being generally available In 1987 with the release of the Acorn Archimedes.

- Hewlett-Packard PA-RISC, introduced in 1986, used in the HP 3000 and 9000 workstations.

- MIPS, introduced in 1986, used by several manufacturers but eventually best known for being used by SGI in e.g. the Iris, Indigo, O2, and Octane models.

- SPARC, introduced in 1987, used by Fujitsu and Sun. Best known are the Sun SPARCstation and UltraSPARC models.

- PowerPC, introduced in 1992, used by Apple in its Power Mac range and IBM in the RS/6000 workstations.

- Alpha, introduced in 1992, used by DEC in its AlphaStation range.

This means that there were quite a number of competing architectures by different manufacturers. One thing united them however: most ran a form of the UNIX operating system. HP had HP-UX, SGI had IRIX, Sun had SunOS and Solaris, IBM had AIX, DEC had OSF/1/Digital UNIX/Tru64 UNIX.

Most of these had a common ancestor in UNIX System V, developed by AT&T. As these also often used the X Window System as base for the graphical user interface, porting applications was relatively simple if a compiler for the programming language that was used (often C) was available. UNIX is and always has been a true multi-tasking and multi-user operating system with networking capabilities, and thus much more powerful than the DOS and Windows versions of its time. It wasn’t until the advent of Windows NT that Microsoft started making inroads in this market.

I want to mention two companies in particular:

SGI

SGI is short for Silicon Graphics, Inc. As the name suggests, their products aimed mostly at the 3D graphics market and were very successful in it. They are maybe most famous for being the brand on which the CGI scenes for the first Jurassic Park movie were created.

During my bachelor and master studies, I worked as student assistant at one the chairs of the geodesy faculty in Stuttgart. They had an SGI Octane that had been purchased for a photogrammetry project. I remember that the manual read “lifting the Octane is a two-man job”. Unfortunately, in 2000, its power wasn’t that impressive anymore, so I never really used it – which is especially sad considering than an Octane originally had a price tag of around US$ 40,000, so about a factor of 10 of what one would have paid for a decent PC. I was offered the Octane at the end of my contract, but with no real use for it and not knowing what to do with this massive piece of hardware (including a large CRT screen, of course) I declined.

Another famous SGI model is the O2. It was an entry-level model, positioned below the Octane. It was shown as one of the devices being possessed by an artificial intelligence in the User Friendly web comic that was popular among computer nerds like me around the turn of the century. I actually briefly owned an old O2 that I found unused at the university, but sold it off as I had no space for it and no intention of getting it up and running.

SGI’s fortunes declined towards the end of the 1990s, as x86 machines (see below) became more powerful while being much cheaper. SGI tried to counter this by introducing Intel-based Linux workstations as well as entering the supercomputer market, but failed. It went bankrupt in 2009, the successor company Silicon Graphic International was acquired by Hewlett Packard Enterprise (HPE) in 2016. Among SGI’s lasting legacy is the OpenGL library for 3D graphics.

Sun

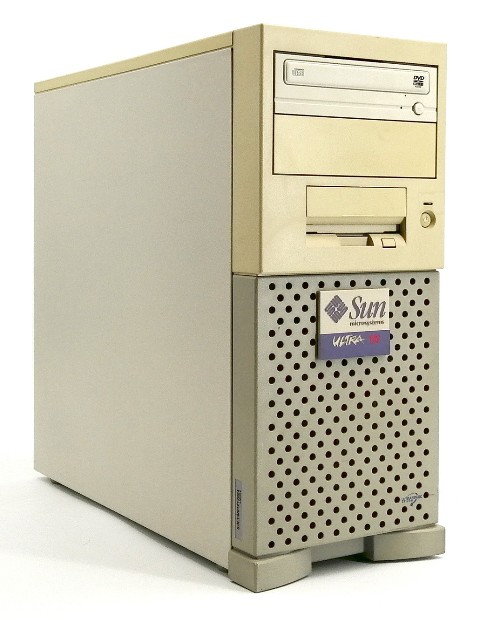

Sun Microsystems was another big player in the workstation market. They are best known for their SPARCstation and UltraSPARC computers, often in a slim “pizza box” case. The UltraSPARCs were 64 bit designs. I at some point had several old SPARCstations, which had the annoying issue that they would always forget all settings due to a dead BIOS buffer battery, so I didn’t really use them.

Much more important to me was the Sun Ultra 10 that was present at the chair where I worked. I had been bought as database server for a project that never materialized, so I put it to use as my personal workstation. I was allowed to replace Solaris with Debian Linux, which made it a lot more useful, as now the entire world of GNU/Linux and Open Source software was available. It wasn’t particularly fast, given that it only had a 333 MHz processor, but it had 1 GB of RAM when my PC only had 128 MB. I used it for several years, running Debian Linux, and wrote much of my master’s thesis on it. I was very disappointed when I wasn’t allowed to take it home at the end of my contract – until I heard in my quiet home, where I had it for a few days to copy data, what a racket the two external SCSI hard drives really made.

Sun has had a lasting impact on the computer world as the company where the Java programming language was created, and open-sourcing StarOffice as OpenOffice, which would eventually spawn LibreOffice, among other innovations. With a strong foothold in servers, Sun held out longer than SGI, but was eventually acquired by Oracle in 2010. The former Sun campus now houses the headquarters of Meta/Facebook.

The rise of x86

As mentioned above, the early IBM PC models and the many clones it spawned were ill-suited to workstation use. They had neither the computing resources nor the graphics capabilities that were required. Up to and including the 80386, they didn’t even have floating-point units in the CPUs, making them painfully slow at floating-point math or requiring the purchase of an expensive math coprocessor. This only changed with the introduction of the Intel i486 in 1989.

But there were other things going on, too. The UNIX/RISC workstations each had their own ecosystem, locking customers in and allowing manufacturers to keep the prices and thus profit margins high. The PC/x86 world on the other hand was open, with many manufacturers building cheap “IBM clones” that in some cases even were better than what IBM had to offer, starting with Compaq being the first company to sell a PC with the 80386 processor. And there was competition on the CPU side, too, with manufacturers like AMD and Cyrix producing their own x86-compatible processors.

The competition on both the CPU and complete computer fronts lead to steady price decreases and performance boosts. By the early 1990s, it became obvious that the architecture that at the time was still called the “IBM compatibles” was destined to be the #1, killing off the Motorola 68000-based home computers such as the Commodore Amiga, seriously threatening the existence of Apple which was very much pushed into a niche, and dominating the world of business computing.

The second half of the decade saw the introduction of several generations of Pentium processors, the first graphics cards for 3D acceleration (previously SGI’s domain), and the beginning of an arms race between Intel and AMD that would reach its peak in the early 2000s. During this “Gigahertz race”, CPU clock frequencies went from 500 MHz to 3 GHz in just a few years. The RISC CPU makers simply couldn’t match this pace, given that they sold much smaller numbers of CPUs over which to recoup the development costs.

The final nail in the coffin was AMD’s introduction of the 64-bit extension for x86, announced in 1999 and available in 2003 with the first Opteron CPU. AMD and Intel quickly struck a licensing deal, enabling Intel to produce compatible CPUs. Importantly, both retained full 32-bit backwards compatibility, something Intel had failed to do with its 64-bit Itanium architecture. With 64-bit addressing, more than 4 GB of memory was now no longer limited to the RISC designs that had been 64-bit for quite some time.

On the software side, things were happening, too. The ever-increasing performance of the x86 CPUs combined with its large number of installed systems, most of them running Windows, made it attractive to port software that had previously only run on the RISCH workstations to x86 and Windows. SGI partly dug its own grave when they released a Windows version of Alias|Wavefront Maya as a response to Microsoft acquiring the competitor Softimage.

The drawback was that Windows had never been taken seriously, even in its NT guise, by people who considered UNIX the only true operating system. But in Finland, a young computer scientist called Linus Torvalds had started to build a UNIX operating system kernel on his 386. Called Linux, version 1.0 was released in 1994.

Linux wasn’t the only, not even the first UNIX for x86. But is was different from the alternatives – it was free as in free beer and it was free as in freedom – i.e. open-source software. And being a new development from the ground up, it did not have to deal with lawsuits that FreeBSD, another open-source x86 UNIX, faced.

Linux quickly gained traction and today is the predominant operating system for both servers and supercomputers. Thanks to Android being based upon Linux, it is the most-used operating system today. Mainstream acceptance on the desktop remains low, but it is very popular in science and software development – classic workstation fields of work.

The Cloud, the return of RISC, and the coming of AI

Thanks to the Internet, everything became connected in the 2000s. In the 1990s, one would connect to the Internet via modem and pay by the minute or megabyte. In the 2000s, broadband and “flat rate” access became the norm. This allowed for a new computer paradigm. It was no longer necessary to run applications on a desktop computer – they could run on a server somewhere and be accessed through a web interface instead. As a matter of fact, that server didn’t even need to be a real server – it could be a “virtual machine”, giving many users their own virtual server without having to know where exactly it was and not having to worry about hardware and reliability.

This has advantages for both the user and the service provider. The user no longer needs powerful hardware and can scale up temporarily when more processing power is required. The service provider, instead of selling hardware once, can bind users through a subscription model. This computing paradigm is known as Cloud Computing.

It has also had an effect on workstations. If your computing power is provided by some server in the cloud, the end-user only needs a computer that is used for remote control and maybe software development. Together with ever-increasing computing power, this has led to portable “laptop” computers being much more common now than the traditional static desktop computer.

When we last encountered RISC, it had been almost completely replaced by x86. Sure, PowerPC soldiered on in IBM’s servers and supercomputers, but even Apple converted to x86 starting in 2005. But a whole new class of devices needed compact, efficient yet powerful processors: smartphones and tablets. RISC turned out to be a good fit for these needs, and then especially one RISC implementation: the one by ARM, which once stood for Acorn RISC Machine, used in the Acorn Archimedes mentioned above.

ARM had long stopped manufacturing processors themselves, focusing instead on designing them and licensing the architecture and design to chip makers. Today an estimated 98% of mobile devices is powered by ARM processors.

For larger computers, the verdict of whether RISC or CISC is better is still out, with x86 still going strong. But ARM has gained ground in servers, including those for AI applications (see below).

On the desktop, Microsoft has tried for a long time with Qualcomm as partner, but another company has been very successful with it. Since 2020, Apple uses ARM processors of their own design for their Mac range of computers and some iPads. This M-range of processors has turned out to be both powerful and power efficient, beating AMD and Intel on both fronts.

AI (artificial intelligence), which really means the use of artificial neural networks, is not exactly new. It has been investigated for decades. Discriminative AI, i.e. the use of AI for interpretation of things like images and measurement results, can also be considered proven technology. But it’s Generative AI that’s in everyone’s mouth. Since the release of OpenAI’s ChatGPT in late 2022, which could be asked in natural language and give answers in same, advances have been quick: better answers, image, video, and even music generation, coding assistance, and reasoning models that operate in steps instead of simple predicting the most likely statistical outcome.

This AI revolution demands two things: data for training its models, and computing power. So much computing power that Nvidia, the most important supplier of AI hardware, has become the most valuable company in the world. And so much electric power that new sites for computing centers are planned next to power stations, with Google even investing in new nuclear reactors.

These demands for computing power have led to an increased interest in workstations. Due to the computational needs and associated costs, the online use of more advanced models generally comes with a subscription fee. Combined with privacy concerns, it can become interesting to self-host generative AI models and even train them yourselves. Not surprisingly, many manufacturers now advertise their more powerful models as “AI workstation”. Nvidia and its partners even sell a mini PC-sized system as personal supercomputer. It is powered by an ARM CPU and Linux.

For most of us, a traditional x86 computer remains the best choice. Intel and AMD have made slightly different choices. In consumer CPUs, Intel uses CPUs with smaller (efficiency) and larger (power) cores to achieve a balance between single-threaded and multi-threaded performance and efficiency, at the cost of complicating scheduling. AMD offers up to 16 identical cores and some models with very large caches – which benefit not only game performance, but also help with some data-intensive tasks such as audio processing.

On the professional side, advertised as workstation or high-end desktop (HEDT) processors, you can get Intel Xeon and AMD Threadripper CPUs. AMD’s Threadripper PRO 9995WX has 96 cores and allows for up to 2 TB of RAM. Now you just need to find a suitable large problem. 🙂